Just Above Midtown - shaking up the 1970s New York art scene

1974, West 57th Street in New York. Inside number 50 Linda Goode Bryant climbs five sets of stairs and unlocks the door to the newest gallery in the art establishment heartland of Midtown Manhattan. Situated at the back of the building, without a single window, the 724 square foot space was distinctly lacking in the usual desirable real estate attributes but 23-year-old Bryant was a powerhouse of vision, energy, determination and flare. She transformed the unpromising space into Just Above Midtown or JAM, a gallery dedicated to promoting the art of black artists and artists of colour.

Several of JAM’s art gallery neighbours were hostile, accusing her of ‘not showing 57th Street work’ but that was the point. She ignored their criticism and dismissed obstacles that artists themselves viewed as insurmountable.

People were saying, ‘They won’t let us.’ I was frustrated by us not letting ourselves. Not understanding that we, in fact, can create what we need. If the doors aren’t being opened for you, then go out and make your own doors. Artists need opportunities for their work to be experienced by others. So let’s just create that.

Linda Goode Bryant

Linda Goode Bryant as an undergraduate, Spelman College, 1968

Inside the gallery it was if a series of experiments were conducted to discover entirely new ways of making and viewing art - Bryant described JAM as ‘a laboratory’. While artists were encouraged to push the boundaries of their imagination and creativity, visitors were presented with a startlingly different idea of what a gallery could - or should - be.

David Hammons b. 1943 first exhibited at JAM in Synthesis, its inaugural show held at the end of 1974. Originally from Springfield, Illinois Hammons moved to Los Angeles aged just 20 and took classes in commercial art and design and then fine art. His early series of “body prints” were made by pressing his head and body, coated with margarine, onto paper then dusting the resulting greasy image with powdered pigment. Many of these body prints – including Injustice Case 1970, (for which he used a model rather than his own body) – focus on racial oppression, a theme he returned to in In the Hood, where the severed black hood resonates with histories of lynching and trophy hunting.

Images: Injustice Case 1970, body print (margarine and powdered pigments) and American flag ©David Hammons/LACMA; Higher Goals 1987 wooden telegraph poles, bottle tops, basketball hoops ©David Hammons/Pinkney Herbert and Jennifer Secor/Public Art Fund; In the Hood 1993, athletic sweatshirt hood with wire, 58.4 x 25.4 x 12.7 cm ©David Hammons/Benoit Pailley/New Museum, New York;Untitled 2000, crystal, brass, frosted glass, light fixtures, hardware and steel, 195.6 x 221 x 63.5 cm ©David Hammons/Phillips

The insatiably curious Hammons has always found New York teeming with inspiration and materials for his work. He creates sculptures made from objects he finds while out walking in his adopted city: chicken bones, bottles and hair swept up from the floors of Harlem barbershops. New York’s public spaces have provided the setting for performance pieces such as Bliz-aard Ball Sale 1983, when he sold snowballs at the side of a Manhattan street; and installations including Higher Goals 1987 in Brooklyn’s Cadman Plaza Park where he studded telephone poles and backboards with thousands of bottle tops for a series of towering basketball hoops that emphasised the importance of not placing limits on aspirations.

“To walk with David is a lesson in seeing, and not just ordinary seeing. He’s a supernatural noticer. He’d draw my attention to people working and the materials they used, and to trash and discarded things, and the relationships between them. You realize how little you see.”

–Ben Okri

© David Hammons/Gemini G.E.L.

Senga Nengudi (b. 1943) conceived her 1970s series, R.S.V.P., in her hometown of Los Angeles. The name of the series chosen as a deliberate invitation to viewers of the works to ‘respond’ to and interpret them in their own way, informed by personal experiences. By using different shades of pantyhose filled with sand Nengudi created sculptures exploring the elasticity of the human - particularly female - body and human psyche. Nengudi’s dance background gives her an acute awareness of the human body in space and many of her works have a performative element as a dancer tugs and stretches the nylon mesh that is tethered to the walls and ceiling. After being introduced to Linda Goode Bryant by David Hammons, Nengudi took part in JAM’s 1978 exhibition The Process As Art: in Situ during which artists made or performed their art in front of gallery visitors.

Images: R.S.V.P. 2003, Pantyhose and sand, 10 pieces ©Senga Nengudi/MoMA; Performance Piece 1978 Black and white photograph ©Harmon Outlaw/Lévy Gorvy Gallery and Thomas Erben Gallery; A.C.Q. (I) 2016-2017 Refrigerator and air conditioner parts, fan, nylon pantyhose, sand. ©Senga Nengudi/ Natalie Hon/ Lévy Gorvy Gallery and Thomas Erben Gallery.

Nengudi has always enjoyed collaborative art-making and is a natural teacher. She spent over ten years teaching in the Visual Art faculty at UCCS (University of Colarado Colorado Springs), immersing herself in its close-knit and mutually supportive community and constantly developing her practice to create new experiences that encourage people to look beyond themselves and to respect and acknowledge others. At the 2017 Venice Biennale she counterbalanced the fluidity and strength of pantyhose with the sharp, brutal rigidity of air conditioning units and refrigerator parts, demonstrating her belief in the potential of the cast aside or overlooked - whether people or objects - to have a new poetic life.

‘I think that within every material and every human being there is the ability to elevate yourself and to become larger than you think you are ……. I believe everybody has a poetic expression and that that expands them to be more than they think they are.’

–Senga Nengudi

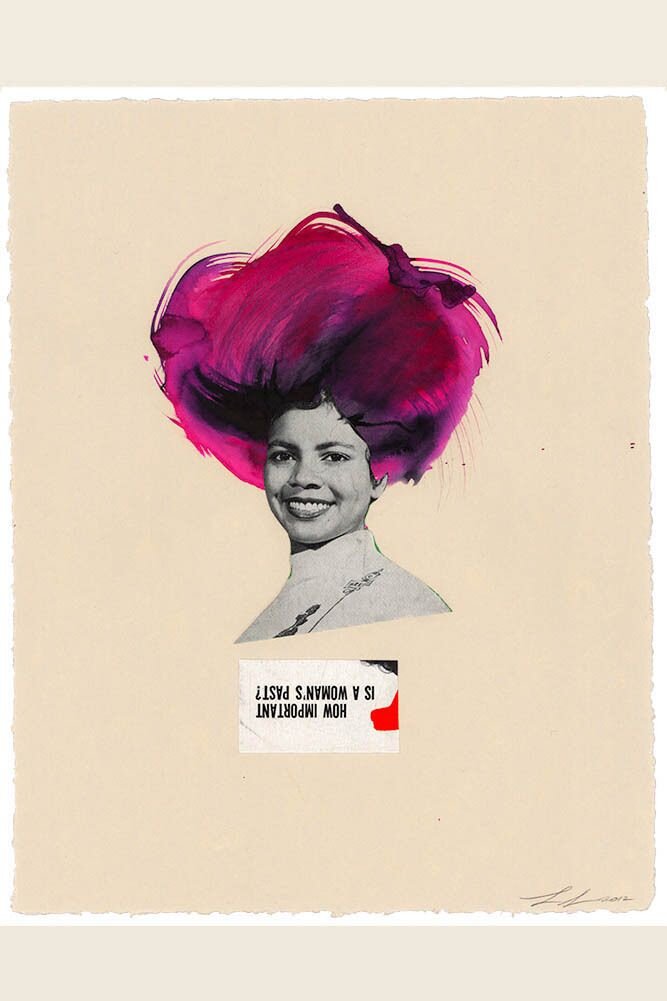

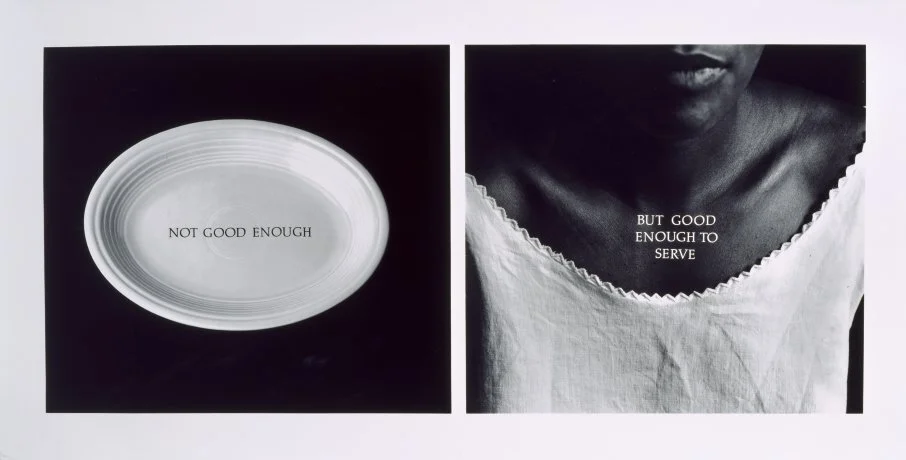

Lorna Simpson (b.1960) lives and works in her native Brooklyn. From the moment she got her first Polaroid camera - by collecting the tokens from Kleenex boxes - she became absorbed by the layers of meaning and ambiguity created by playing with and manipulating photographs. Simpson studied first at the School of Visual Arts in Manhattan then, during postgraduate study at the University of California, San Diego, developed her practice as a conceptual photographer - pairing images with text to explore ideas of representation, identity, gender, race and history In 1986, just a year after graduating, she had her first New York exhibition, Screens, at JAM.

Images: Five Day Forecast photographs, gelatin silver print on paper and 15 engraved plaques ©Lorna Simpson/TATE; Jet past 2012; collage and ink on paper 28.4 x 22.1 cm ©Lorna Simpson/Hauser and Wirth C-Rations 1991, gelatin silver print on paper, Image 1:48 x 53.3 cm Image 2 48 x 53.5 cm ©Lorna Simpson, Museo Reina Sofia; Lyra night sky styled in NYC 2020, collage on paper ©Lorna Simpson/Hauser & Wirth.

Simpson’s visually arresting collages frequently combine portraits from 1950s, 60s and 70s editions of Jet and Ebony magazines with printed, photographic and painted elements to create images with ever-evolving associations. In the past decade her practice has expanded into painting and sculpture and in 2019 she was awarded the J.Paul Getty Medal in 2019 for her ‘extraordinary contribution to the practice, understanding, and support of the arts and humanities’. During quarantine Simpson has created surreal portraits including Lyra night sky styled in NYC 2020 in which the shape of the woman’s bouffant bob hairstyle has been replaced with a cut-out section of a diagram of the night sky showing – coincidentally - the constellation Corona Borealis.

“My interests were always about removal of societal boundaries in the way we talk about race or the way we talk about gender or sexuality, because it’s so ingrained even in the language we use.”

–Lorna Simpson

After more than two decades and having nurtured and promoted the early careers of many of today’s most renowned artists, Just About Midtown closed its doors in 1986 when Linda Goode Bryant became disillusioned with the investment-oriented state of the art world. She turned her creativity and energies towards make films including, with Laura Poitras, Flag Wars, an Emmy-nominated documentary about the white gentrification of a working-class black neighbourhood in Bryant’s hometown of Columbus, Ohio. Just over ten years ago she started Project EATS in New York, an art and city farming neighbourhood-based project. Bryant is creating spaces in the heart of the city that are changing lives - just as she did in 1974 when she started JAM.

‘Art is as essential as air and water and food. It is for our soul – that thing that connects us universally. And reminds us what we’re responsible for – the world we need to live in.”

–Linda Goode Bryant

Ben Okri’s quotation comes from ‘David Hammons follows his own rules’ by Calvin Tomkins in The New Yorker, December 2nd, 2019. You can read a conversation between Linda Goode Bryant and Senga Nengudi here. Further works: David Hammons, Senga Nengudi, Lorna Simpson. The exhibition Just Above Midtown: 1974 to the Present is scheduled to be held at MoMA in 2022.