Stridentism: A Post-Revolutionary Mexican Movement

Stridentism is an aftermath of the Mexican Revolution. It followed a European model to define what the cultural future of the city would be, post-revolution. Let’s look at the visual language of the movement as well as how it came about.

During the immediate post-revolutionary period, Mexico plunged into a phase of rapid modernisation that became a revelation for intellectuals and poets. Maples Arce was the literary pioneer who dared to publish a flamboyant manifesto, 1921, (below) to call upon young artists to start an aesthetic revolution against the standardisation of imagination. As many other literary avant-garde movements in Latin America, Stridentism remained neglected for over fifty years after its emergence in 1921, leaving the archive full of gaps and mysteries waiting to be solved.

Below: Magazine layouts Portadas de la revista Irradiador Nº 1 (septiembre de 1923), Portadas de la revista Irradiador Nº 2 (octubre de 1923), Portadas de la revista Irradiador Nº 3 (noviembre de 1923).

The Stridentist movement lasted a few years and then faded abruptly in the midst of political upheaval, nevertheless the evidence was preserved in private archives and remote libraries until the rediscovery of the movement in 1970 through the work of foreigners in Mexico. The archaeological project of Luis Mario Schneider was followed by other scholars, particularly by art historians interested in the resonance of Stridentism with other avant-garde movements happening in Europe such as Futurism, Dadaism, Cubism and Ultraism. By the end of the movement, many of its integrants had to leave the country for political circumstances but their work continued and the anecdotes of their days as “noise makers” remained in memoirs and interviews that would transcend and reach a new momentum during the twenty-first century.

El Cafe de Nadie, by Ramón Alva de la Canal

Their vision of modernity was so strident that in the following years other interpreters of urban fiction used their visionary aesthetics to translate futuristic ideals into architecture and visual art. (The house of Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera, designed by Juan O’Gorman, 1931 is a clear example of this.)

The house and studio in Mexico City was designed by Juan O’Gorman, who was commissioned by Rivera in 1931. It is one of the earliest modernist buildings in Mexico, and today operates as a museum

Source: The Modern House

As many other literary avant-garde movements in Latin America, Stridentism remained neglected for over fifty years after its emergence in 1921, leaving the archive full of gaps and mysteries waiting to be solved. Mexico’s rapid modernisation inspired Stridentist writers to study the European avant-garde movements and create a new language for modernity. Stridentism tended towards an urban sensitivity that imitated the rhythm, speed and even sounds of modern life. It was a movement about lyric provocation, essentially devoted to literature yet it attracted many visual artists who contributed to the movement with illustrations and graphic experimentations.

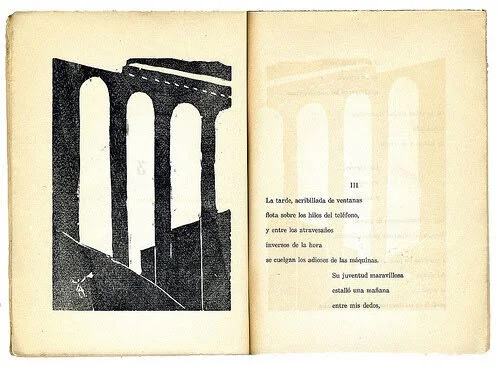

Above: Book Cover: Urbe (Super-poema bolchevique en 5 cantos), Print: Stridentopolis, by Ramón Alva de la Canal. Inside pages, images Courtesy of Urbanisticka.

“The Stridentist manifestos were polysemous texts involving a mixture of anger and humour, iconoclasm and sincerity. Dealing a “crushing blow” to the cultural establishment, which perceived Stridentism as “insane asylum” and “nightmare”, their aim was to free artists and writers from the weight of convention, giving rise to clown-like play with language and images and, in general, literary and artistic experimentation and freedom”.

“Optical and auditory games that oppose the silence desired by the poet to listen to his feelings to the noise coming from reality.”

Rashkin, Elissa J, (2009) The Stridentist movement in Mexico, Lexington Books, Plymouth UK

Thank you to Mexican artist Mylene Dosal who shared her research and love of Stridentism. Further reading: here, here and here.